The Story of Kalidasa: India's Greatest Poet

Kalidasa, whose name translates to "servant of the Goddess Kali," is widely considered the greatest poet and dramatist in the Sanskrit language. His life, shrouded in the mists of antiquity, is a vibrant tapestry woven from historical fragments, literary genius, and enduring legends that highlight his transformation from a simpleton to a court jewel. Though his exact dates are debated, he is generally believed to have flourished during the reign of the Gupta Emperor Chandragupta II (c. 380–415 CE), a period often described as the Golden Age of India.

The Legend of the Simpleton

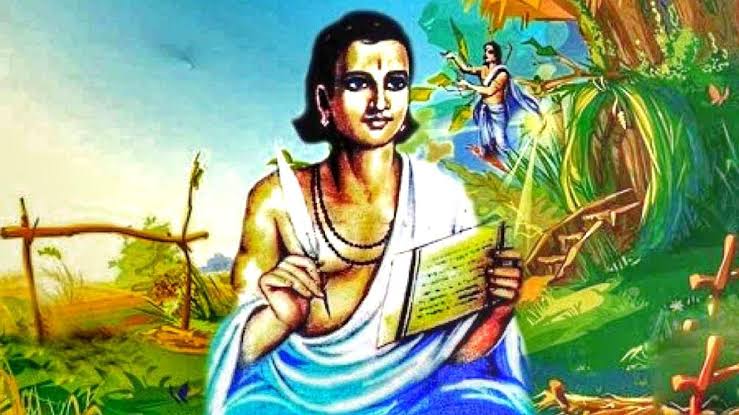

The most popular and enduring legend about Kalidasa's early life paints him not as an educated scholar, but as a village simpleton—a beautiful yet utterly unlettered and foolish young man.

The King's Daughter and the Pundits

The story begins with a princess, sometimes identified as Vidyottama (meaning "excelling in knowledge"), the daughter of a king. She was an extraordinarily beautiful and brilliant scholar, deeply proud of her intellectual prowess. She vowed to marry only the man who could defeat her in a scholarly debate (shastrartha).

One by one, the most learned pundits and scholars of the kingdom challenged her, and one by one, she soundly defeated them. Humiliated by her brilliance and arrogance, the defeated scholars conspired to find an equally foolish man to trick her into marriage, thereby destroying her pride.

They scoured the countryside and found the handsome but ignorant young man who would become Kalidasa, sitting on a tree branch and famously sawing off the very branch he was sitting on . Seeing this act of supreme foolishness confirmed he was the perfect instrument for their revenge.

The Silent Debate

The pundits dressed the simpleton in fine robes, instructed him to remain completely silent, and presented him to the princess as the greatest scholar of their age, who had taken a vow of silence (Mauna Vrata). The princess, accepting the challenge, proposed a silent debate using gestures.

* The princess, to test his understanding of the ultimate truth (Brahman), raised one finger, symbolizing the one absolute reality.

* The simpleton, mistaking her gesture for a threat to poke his eye out, countered by raising two fingers, symbolizing his intent to poke out both of her eyes.

* The conniving pundits interpreted this brilliantly for the princess: "O Princess, he says that while you speak of the One Ultimate Reality, he argues that the world cannot be understood without the union of Purusha (consciousness) and Prakriti (matter), thus proving the dualistic nature of creation."

* Next, the princess raised five fingers, symbolizing the five elements (Pancha Mahabhutas).

* The simpleton, who had been hungry, mistook this for an offering of a slap with an open palm. In response, he raised a clenched fist, indicating he would punch her back.

* The pundits again intervened: "O Princess, he argues that while the five elements are individual entities, they are meaningless until they come together to form one unified creation—the fist."

Astounded by this profound "philosophical interpretation," the princess conceded defeat and married the simpleton.

The Transformation

The truth, however, could not be hidden for long. On their wedding night, when the princess asked her husband a simple question, his crude, ungrammatical response revealed his absolute lack of learning. Deeply hurt and enraged by the deception, she cast him out of the house, perhaps telling him, "If you want to live with me, you must first acquire knowledge and fame."

Driven by her rejection, the distraught young man sought solace and guidance. He is said to have gone to a temple dedicated to the Goddess Kali, whose name he later took. Through intense penance and devotion, he begged the Goddess for knowledge. The Goddess, moved by his devotion, is said to have blessed him by touching his tongue with her sacred mark or pen, instantly bestowing upon him immense wisdom, poetic genius, and a mastery of the Sanskrit language.

Returning to his wife a transformed man, he demonstrated his new poetic skill. The first verse he is said to have uttered began with the words, "Asti Kashchid Vāgvisheshah," which means, "Is there something special in your speech?" This legend is often cited to explain the profound depth and complexity of his poetry, suggesting divine intervention was required for such genius.

The Jewels of Ujjain: Kalidasa in the Court of Vikramaditya

After his transformation, Kalidasa's fame spread rapidly, and he found a place in the court of a great king. Though historically placed under Chandragupta II, he is most frequently associated in legends with the mythical King Vikramaditya of Ujjain . Ujjain was a city renowned for its learning and culture, and King Vikramaditya’s court was famous for the Nine Gems (Navaratnas), a council of nine extraordinary scholars, artists, and scientists. Kalidasa was foremost among them.

His life at court was one of immense prestige, where he flourished as a poet, dramatist, and connoisseur of life. His works reflect a deep appreciation for the beauty of nature, the complexities of human emotion, and a profound reverence for Hindu mythology.

The Masterworks of Kalidasa

Kalidasa's literary output is broadly categorized into three Plays (Nataka), two Epic Poems (Mahakavya), and two Minor Poems (Khandakavya). They are celebrated for their Rasa (aesthetic flavour), Alankara (figures of speech), and Chandas (metres).

The Three Plays (Nataka)

* Abhijñānaśākuntalam (The Recognition of Śakuntalā):

* The Story: This is universally regarded as his greatest masterpiece and one of the finest dramas in world literature. It tells the story of King Dushyanta and the ascetic maiden Śakuntalā, the daughter of the sage Vishwamitra and the celestial nymph Menaka. They meet in a hermitage and fall instantly in love, marrying in a secret ceremony (gandharva vivaha).

* The Curse: Dushyanta returns to his capital promising to fetch her later. Śakuntalā, lost in the thought of her husband, unknowingly offends the irritable Sage Durvāsa, who curses her: her beloved will forget her completely until he sees a token of recognition he gave her.

* The Ring: On her journey to the King's court, Śakuntalā loses the signet ring given to her by Dushyanta in a sacred pool. When she appears before the King, he does not recognize her, and she is left heartbroken. The ring is later found by a fisherman and presented to the King, which instantly breaks the curse and restores his memory. Filled with remorse, Dushyanta searches for her and eventually finds her and their son, Bharata, a name that would later be given to the nation of India.

* Mālavikāgnimitram (Mālavikā and Agnimitra):

* This is Kalidasa's first play, a romantic comedy concerning the love affair between King Agnimitra of the Shunga dynasty and a beautiful royal handmaiden named Mālavikā. The play focuses on court intrigue, jealousy, and the King's effort to win Mālavikā's love, culminating in their union.

* Vikramōrvaśīyam (Urvashi Won by Valour):

* This drama tells the legendary love story of the mortal King Purūravas and the celestial nymph Urvashi. The play is filled with lyrical poetry and deals with themes of immortal love, separation, and reunion, involving a curse that temporarily turns Urvashi into a vine.

The Two Epic Poems (Mahakavya)

* Kumārasambhava (The Birth of the War God):

* This epic narrates the events leading to the birth of Kumara (Kartikeya), the God of War. The poem beautifully describes the courtship and marriage of Lord Shiva and Parvati, including Parvati's intense penance to win Shiva's affection and the subsequent burning of Kāmadeva (the God of Desire) by Shiva's third eye. The narrative stops just short of Kartikeya's birth, though some later chapters are traditionally ascribed to Kalidasa.

* Raghuvamśa (The Dynasty of Raghu):

* A magnificent historical epic, it recounts the lineage of the Raghu dynasty—the Solar Dynasty of Ayodhya—from its founder Dilipa all the way to Lord Rama and his descendants. The poem is a comprehensive chronicle of the noble kings, their virtuous rule, their conquests, and their ultimate piety. It is revered for its sophisticated language and detailed depiction of royal life and Dharma (righteous duty).

The Two Minor Poems (Khandakavya)

* Meghadūta (The Cloud Messenger):

* This is arguably the most famous and influential example of a Khandakavya (lyric or minor poem). It is a poignant, descriptive poem of approximately 111 stanzas.

* The Plot: A Yakṣa (a nature spirit), exiled by his master Kubera for neglecting his duties, pines for his beloved wife in the distant Himalayas. During the monsoon season, the Yakṣa is overcome by sorrow and pleads with a passing cloud to carry his message of love and longing to his wife.

* The Journey: The rest of the poem is a breathtaking description of the cloud's journey across the heartland of India, detailing the magnificent landscapes, rivers, mountains, and cities it passes over, transforming the simple message into a vivid geographical and emotional journey.

* Ṛtusaṃhāra (The Gathering of the Seasons):

* This is a descriptive poem that chronicles the six Indian seasons—Summer, Monsoon, Autumn, Early Winter, Winter, and Spring—and their effect on nature and human emotions, particularly those of lovers. It is a work of pure sensory delight, praising the natural world.

The Legacy and Disappearance

Kalidasa’s influence on Indian and world literature is immeasurable. His use of classical Sanskrit is considered the epitome of elegance and complexity. He mastered the technique of Upamā (similes) and Arthantaranyāsa (gnomic statements), which brought a unique richness and clarity to his descriptions. The depth of human feeling in his works, particularly the tender and compassionate portrayal of love and separation, ensures his lasting relevance.

The end of Kalidasa's life is, like his beginning, shrouded in mystery and legend. One popular account suggests he traveled to the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to visit the court of King Kumāradāsa. There, he supposedly became embroiled in a tragic court intrigue involving a courtesan and a clever riddle. He was murdered for his brilliance, and the news of his death caused great grief to King Kumāradāsa, who is said to have immolated himself on Kalidasa’s funeral pyre.

However, the most fitting end for a man whose life was a series of profound transformations is that he simply vanished into the literary cosmos he helped create. He remains the Kavikula Guru (The Master Poet of Poets), the eternal shining star of Sanskrit literature.

His story is not just one of a poet's life, but a testament to the power of transformation, the pursuit of knowledge, and the enduring beauty of art. From the simpleton sawing his own branch to the court jewel penning the Abhijñānaśākuntalam, Kalidasa’s life itself is a sublime epic, a true gift to humanity.