In the early 18th century, merchants from the port city of Ostend (now in Belgium) observed the astronomical wealth being generated by the Dutch and British East India companies. At that time, this region of Belgium was under the Habsburg Empire of Austria.

In 1722, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI granted an official charter to the "Ostend Company." This move was seen as a direct and provocative challenge to the long-standing maritime monopolies held by the Dutch and the British.

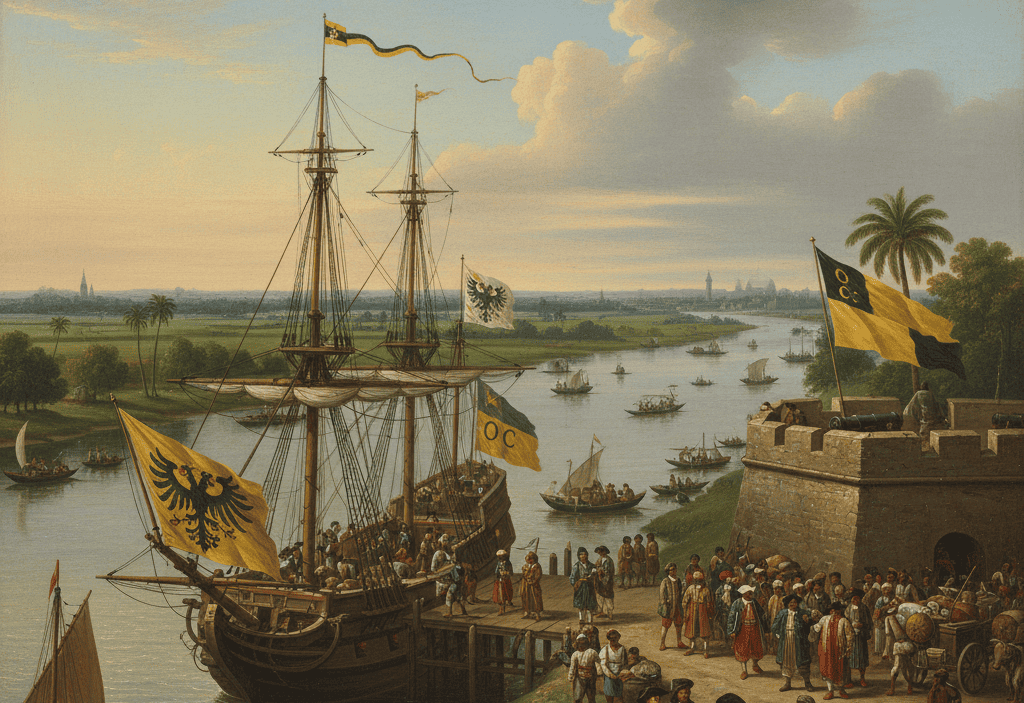

The ships of the Ostend Company were drawn to the fertile and lucrative shores of Bengal. They established two primary centers in India:

Bankibazar: Located on the banks of the Hooghly River, near Calcutta (Kolkata). This served as their main trading hub and featured a fortified factory.

Covelong (Kovalam): They established another factory on the Coromandel Coast, near Madras (Chennai).

Mirroring the strategies of the Danish and Swedish companies, the Ostend Company focused heavily on the export of tea, silk, fine muslin, and spices.

The Ostend Company achieved startling success in its early years. The goods brought back by their ships were sold in European markets at lower prices and often with higher quality than those of their competitors. This efficiency caused significant alarm within the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

The British and Dutch feared that if this "new player" were not stopped, it would grow into a major threat to their established commercial empires.

Defeating the Ostend Company on the battlefield was difficult and risked a wider European war. Consequently, the British and Dutch turned to diplomacy. They exerted immense pressure on Emperor Charles VI.

At the time, Charles VI had no male heir and was desperate to ensure that his daughter, Maria Theresa, would succeed him on the throne. To secure the recognition of this succession (known as the Pragmatic Sanction) from the major European powers—especially Britain and the Netherlands—he needed their political support.

In 1731, under the Treaty of Vienna, the Emperor agreed to sacrifice the Ostend Company in exchange for the recognition of his daughter’s right to rule.

The company's charter was suspended in 1731, and by 1744, it had completely ceased to exist. Their employees at Bankibazar in Bengal faced combined pressure from local Nawabs and British naval intimidation. Ultimately, the Belgian merchants were forced to abandon their Indian dreams and return home.

While the Ostend Company’s history in India spanned barely a decade, it offers a vital historical lesson. It demonstrates that in 18th-century India, trade was never just about economics; it was deeply intertwined with European high diplomacy and dynastic politics.

Today, it is difficult to find physical remnants of this brief Belgian influence in Bankibazar (West Bengal), but in historical archives, the company is recorded as a "spark" that momentarily sent shockwaves through the global superpowers of the era.

The story of the Ostend Company is one of a "failed" but "brilliant" venture. It reminds us that India’s soil was not just a playground for the great imperial armies, but also a destination for bold merchants from smaller corners of Europe who were willing to risk everything for a stake in the East.